13 Dec 2017

Adventures in Dalbergia

"I cannot smell the aroma of my studio. But when people walk in, the first thing they do is comment on the woody scent that fills the air,” says Venezuelan born Federico Méndez-Castro sitting opposite me in his studio on Granville Island, an artists’ hub in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. “It would be impossible for me to have something like this in New York City or Paris.”

Three days earlier I had wandered past Federico’s glass fronted space and stopped dead to marvel at his work through the window. As I stepped into the open white space, the sound of a sander, hard at work, stopped. Moments later I was warmly greeted by Federico, his lyrical Latin accent and thick rimmed spectacles immediately giving him the air of a man with a thousand stories to tell. He spoke passionately about his work – about his favourite chair by Gio Ponti (which stands proud, shrine-like, in his studio) and his hero, Professor of Furniture Design at The Royal College of Art and Master Craftsman David Pye. Before long he was bolting up and down his stairway to retrieve various books that he was adamant I should read. It was clear that this man has an enduring enthusiasm for his craft. I asked him then and there if I could return in a few days’ time for a lengthier discussion about his life, career and work ...

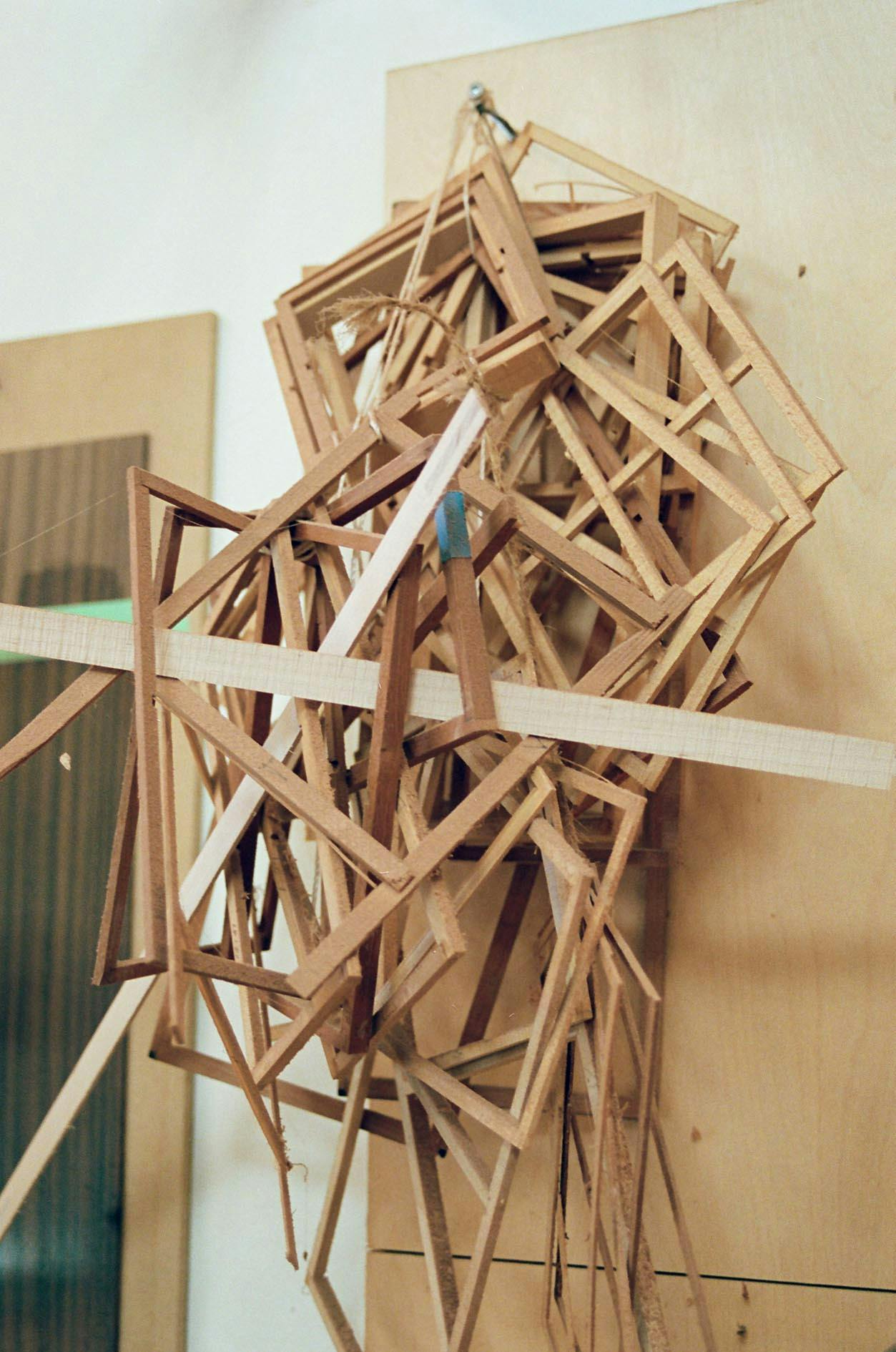

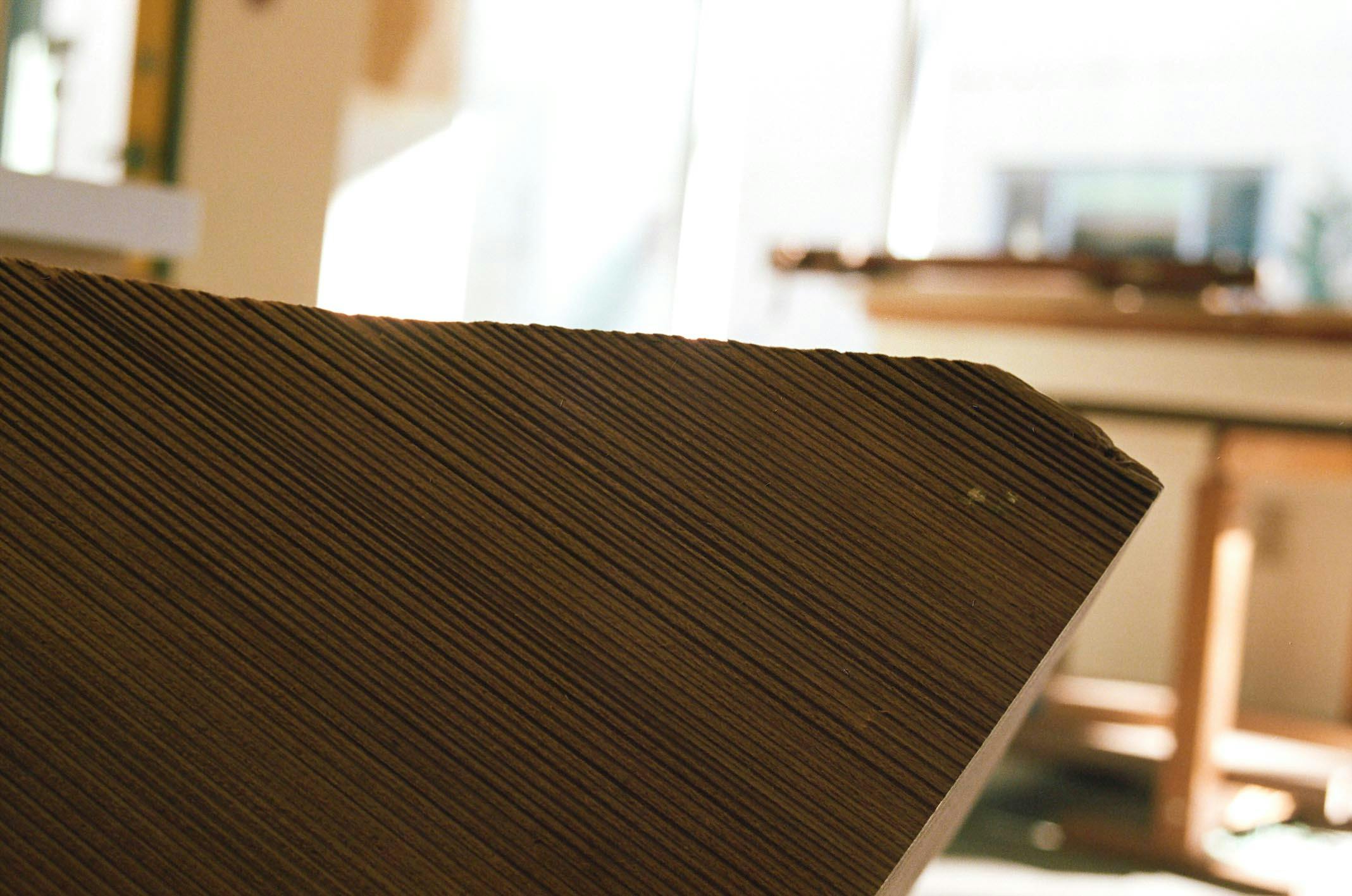

"Right now, I feel like this is the perfect location. I’ve been working in Vancouver for five years, and the fact that I already have clients all over the world is something I’m very proud of,” he explains on my return. Surrounding us is an immaculately maintained space full of geometric and obtusely shaped sculptures, tables, chairs and other seemingly spurious objects – all produced using Federico’s trademark material of Dalbergia wood, otherwise known as Rose wood.

"I’m honest with everything I do, I give the work my total energy. I work seven days a week, ten or twelve hours a day” he explains. I ask him where his work ethic comes from, and he explains his roots as a practicing lawyer back in his home-town of Caracas in Venezuela, before bringing his family to Canada to follow his dream of fine dust making. Once in North America, he studied with the Krenovians at the Inside Passage School of Fine Woodworking.

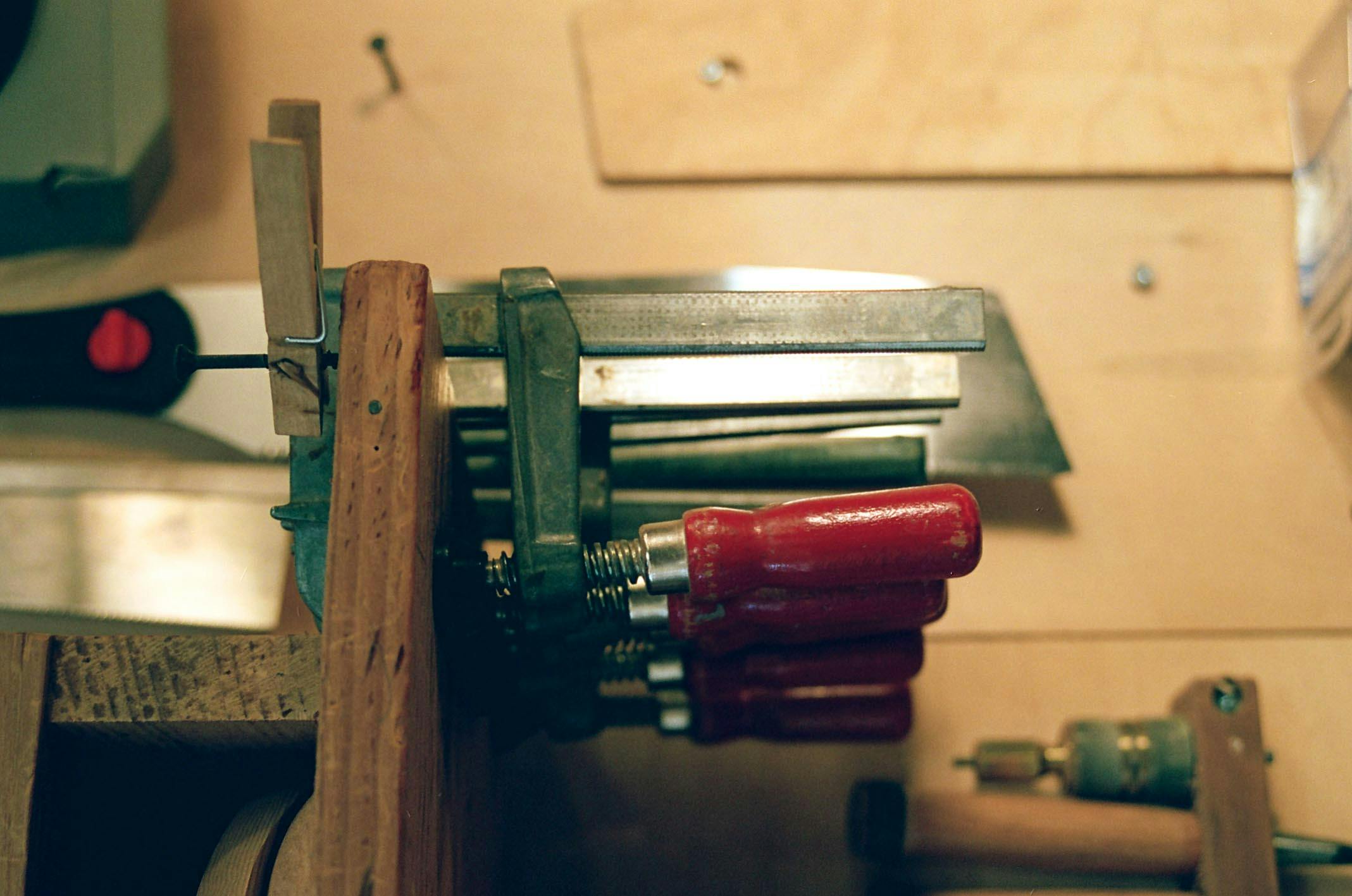

"In the first two months you learn how to make all of your own hand tools. Some of which are the same designs used by cabinet makers centuries ago.” It seems this traditional means of learning and graduation is important to him.

“During my studies, I learned very quickly that there is a lot of confusion about how people define art these days. There is a lot of art without craftsmanship, without training and risk which I don’t like. If you’re a painter, the first thing you learn is how to mix colours, how to interact with the canvas and how to draw lines and curves. It’s the same thing with my craft, and that starts with producing your own tools – the more you’re in tune with your specialty, the more options you will have later in terms of design.”

'It’s like the pain you get when your molar teeth come through. You don’t know that this part of your mouth exists until you start feeling that pain'

These are the sentiments of a true artisan, and he speaks with fervour. Yet, as an immigrant in Canada, he confesses he initially felt guilty about speaking English, “feeling as though he was someone else”. But he soon recognised the importance of being able to express himself through a common language with the same amount of freedom that he has in the creation of his pieces.

"The good thing about being an immigrant and an oddball is that I can feel a sense of isolation; that’s a very good place for me to exist. There are no distractions, and when it comes to my work I can just pay attention to that. But you also have to deal with new people, food and language. You have to use mental processes that I would have never had the opportunity to explore if I’d have stayed in my home town with all the familiarities around me.”

With a history of mental illness in his family, Federico chooses to live a clean lifestyle – "no smoking, no drinking, no drugs” – to keep his mind as uncluttered as possible. "I'm always thinking that I would probably be diagnosed with ADHD if I was assessed today. I’m always asking myself things like, what if I go shorter, longer or more obtuse' with whatever I’m currently working on. The questions never really stop. I always joke with my friends that one morning I will open my doors and find a Mona Lisa waiting for me.”

That ability to engage with his projects with such depth and total abandonment is critical to Federico’s work. “In order to love and be skilled at what you do, you have to get very deep into the knowledge of the subject, and this obviously requires a huge amount of energy. You have to be able to close your eyes and embrace your darkness, and when it comes to creation you have to have certain conditions. One of those is a good sense of individuality. You have to feel you’re an immigrant on this planet.

“It’s like the pain you get when your molar teeth come through. You don’t know that this part of your mouth exists until you start feeling that pain. To be able to show people ‘this is me’ through an object, I have to know myself really well and possess a real sense of individuality and freedom. This is the great thing about Canada, the extension of freedom that you have here is wonderful.”

That freedom was hard fought. A complete change in career preceded his move, and it took a great deal of courage and determination to see it through and convince others of his choice. For Federico, inspiration and drive came in the form of a desire not to form part of the predictable, unimpassioned rat race. "I saw a lot of people working in jobs they didn't like. I realised that if I had faith and worked in what I’m passionate about, sooner or later the rewards would come.

“My aim is to make people’s world that little bit nicer. If you start to imagine the poetry of the space that you exist in, it’s very important that you're surrounded by objects, colours, shapes and proportions that tell you 'come back, this is your unique place’ and that welcome you home every time you step through the door.”

There’s a great deal of humility at the core of Federico’s passion and craft. But as international clients begin to mount up, what of commercial success? “It’s a great feeling when someone buys a piece and exchanges their money for something I have made, it’s a very fulfilling trade. But I don’t think my creative intentions are first and foremost linked to making money. I always like to go to the frontline of the creative battlefield, meaning I allow myself the freedom to do projects that I feel passionately about.

“I was reading about Giacometti the other day. One of his pieces was sold for $120m in 2015. He lived and worked in a tiny studio and never thought his art would sell for anything, so he lived with no expenses to remain free and create the work that he wanted. He was in communion with his art which I think is a really wonderful concept.”

That idea of communion – of an obsession with a craft that is rooted in near spiritual-like engagement – brings us to a more moralistic theme about the limitations of modern society and their impact on artists like Federico. “You can be the type of person who wants to work for a big corporation and change the world in that way, but there should be more people like me working in other fields. Otherwise everything is going to become very boring.

“The world is becoming homogenised by machines. It’s shocking to see the level of consumption of useless objects and resources being used to build them. A machine could do the work of 100 ordinary people, but an extraordinary person could make the work of 100 machines, and art should be like this. You never dance to a song or eat a meal made entirely by a computer, there are some fields where technological interruption just doesn’t work."

Federico's favourite chair, the '699' by Gio Ponti

I’m struck by his sharp opinions on what he calls “the dehumanisation of the creative process”; something all-too relevant across today’s consumer facing creative industries. “Sometimes I spend three days on a design I don’t like, but that process can open doors to new inspiration. When I visit my sister in Paris, I go to the flea market and spend around 25 minutes looking at the corners of art nouveau chairs. It was amazing what they did in those days, they had amazing resources and something we don’t have which is mental time. They were able to spend a week making a small piece of furniture. This rarely happens in the high-speed world we live in nowadays".

Federico is one of many creatives working hard to keep hand craft alive, rallying against the homogenous forces that haunt many creative disciplines today. He seeks to make bold strides forwards at every opportunity, and I end our chat by asking him what the future holds.

“To show my work in galleries all across the world. For that to happen I need money and time, but for little old me from Venezuela, Vancouver really feels like my New York or Paris already. The fact that I’ve been so welcomed and supported in Canada is something I’m hugely grateful for and it of course allows me to do this thing which I love. For that reason, I can be patient for the next chapter to happen organically. I’m not dreaming either, I’d prefer to wait and really establish myself within the concept of my work.

“People who love what they do seem to live for a long time. Hans J. Wegner was 93 when he died, Wendell Castle is still alive and he's 84; it’s amazing the amount of crafts-people who live to nearly 100 years old. You look in their eyes and think 'these people know something about happiness that I don’t yet know’, but I intend to find out, soon enough!”

- Federico Méndez-Castro was interviewed and photographed by Samuel John Weeks

- Edited by Hugo Dawson

- http://dalbergia.ca/ - Discover more of Federico's world here ...